Synopsis: Inheriting an entire holding property to be developed in a floating community and accordance with establish standards for wastewater treatment to preserve and protect the sanctity of marine life and water quality of Imago Bay.

Application: The MarineFAST® adheres to the establish standards for wastewater treatment that could be implemented for floating homes and ultimately be adopted all along the offshore and coastal properties.

The day had been a messy mix of client meetings, last-minute revisions, lengthy phone calls, even lengthier site visits, and—or so it seemed to Ted Whitaker—little actual work accomplished. Now the day’s chaos seemed to be fading with the sunlight. Ted was logging out of the server when the shrill sound of the night phone broke the silence. Once again, he was last to leave. He was tempted to let the call go to voice mail; instead he sighed and reached for the phone.

“Ted Whitaker,” he said, hoping it wasn’t a client with an emergency.

“Mr. Whitaker, this is Arnold Freeburg, of Freeburg and Pomeroy, attorneys at law. We represent the estate of Mr. Barnaby Willis.”

“Barnaby Wil—wait, are you saying Ol’ Barnacle is…dead?”

“Um, yes, I assumed you already knew, since you are a named beneficiary. Were you close?

“Beneficiary? That can’t be right! And no, we were not close. In fact, I’d say the old fellow actively disliked me.”

There was only a slight pause. “I assure you, Mr. Whitaker, you are definitely a beneficiary. I was hoping you would be available tomorrow to discuss Mr. Willis’ last will and testament.”

Ted glanced at his packed calendar. “Tomorrow’s really not good, I—”

“I assure you, Mr. Whitaker, it’s of utmost importance that we meet. One p.m. seems agreeable for everyone else. Please make every effort to accommodate this.“

Everyone else? Ted imagined an office filled with tearful relatives or, worse, bickering, selfish ones. He took another look at his calendar. Maybe I can move the Bryan meeting and have Renee cover the zoning hearing, he thought. He sighed again and said, “I can make one o’clock work. What is your office

address?”

“Oh, no, Mr. Whitaker, we’ll be meeting on Mr. Willis’ boat. He was quite adamant about that.”

“On the Rubicon? Are you serious?”

“Quite serious, Mr. Whitaker. We’ll see you at one o’clock.”

Ted quickly left messages to his colleagues to free up the time. He was a little annoyed at the intrusion and the attorney’s insistence, but mostly he was intrigued. What could Ol’ Barnacle have left him? And why?

He thought back to their first meeting, fifteen years ago. He was working at his grandfather’s development firm as he had in summers past. His grandfather had taken an uncharacteristic afternoon off work and insisted that Ted accompany him. Soon they were on his grandfather’s runabout, trolling the shoreline of Imago Bay. Ted was delighted. He loved the bay, felt more at home there than anywhere. The Whitaker family had owned bayfront property going back several generations. It was considered by some to be the most picturesque shoreline in the entire northwest. But it had remained undeveloped, largely due to the fact that a big chunk of the waterfront, smack dab in the middle of Imago Bay, was the property of Barnaby Willis. He kept his ancient boat, the Rubicon, moored to an equally ancient dock. He lived aboard and was reclusive to the point that this part of the cove was often referred to by locals as the hermitage.

To Ted’s surprise, his grandfather pulled alongside the old dock and, cutting the boat’s motor, gently glided to a mooring post. He motioned for Ted to jump on the dock and threw him a line to tie off the boat. Then his grandfather grabbed his satchel and stepped onto the dock.

“Grandfather, why are we here? Haven’t you told me and my friends to stay away from Ol’ Barnacle, that we might be shot?”

His grandfather shook his head and said, “I asked you not to call him that.” Then he smiled and whispered, “Observe and learn.”

“Observe and learn” was his grandfather’s mantra. Ted knew it also meant, “Shut up and listen.” It allowed him to unobtrusively attend many of his grandfather’s board meetings, client negotiations, and even some heated power brokering deals, soaking up practical knowledge that he would one day feel rivaled anything he learned at business school.

Ted silently followed his grandfather as he casually tapped three times on the side of the hull, then made his way aboard.

A voice came thundering from inside the boat. “Winston Whitaker, you old reprobate! You’d better have a good reason for disturbing the solitude of my sovereign territory of Imago Bay.”

Ted’s grandfather reached into his satchel and brought out a magnum of champagne and handed it to Barnaby Willis. “I thought it was time you met my grandson, Theodore.”

Ted remembered the sharp look of scorn Barnaby gave him that day. “Yes, I’ve heard him and his loud friends frolicking in the bay. Doesn’t your family teach its younger generation any manners?”

Ted bit his lip to keep from replying, but his grandfather merely chuckled and began talking to the recluse about fishing and water traffic and countless other marine topics as they sat on the deck’s worn benches. Finally, Winston stood, reached for his satchel and, almost as an afterthought, asked, “Have you given any thought to my offer, Barnaby?”

The old hermit snorted, “Winston, I have no need of your money. And I’ve no intention to sell to you or anyone. But thanks for the grape juice.”

The visit would repeat itself annually over the next decade, with Ted accompanying his grandfather, and being virtually ignored after stepping aboard the Rubicon. Each year the same offer was mentioned and every year summarily dismissed.

When his grandfather died suddenly five years ago, Ted found himself at the helm of his grandfather’s Whitaker Developments and the sole owner of the family’s Imago Bay property. There was a stipulation, however, that the land was not to be developed as long as Barnaby Willis held his “sovereign interest” in the Bay.

In a personal letter that his grandfather’s attorney handed him, Winston urged Ted to continue the annual visits to the old man, the annual gifts of champagne, and the annual inquiry about buying the property. And Ted complied. The answer from the recluse was always a scornful “NO!” and an acerbic reply that the Whitaker family should not expect to own everything.

Ted always kept the visits as short as decency allowed but was inevitably surprised when the old man asked pointed—and uncannily insightful—questions about Ted’s latest projects at Whitaker Developments:

“Tell me, was it really your idea to put a green roof on the new library?”

“Do you do a life-cycle assessment for all your clients—or only the wealthiest ones?”

“How do you propose to control rainwater runoff at that monstrosity of a performing arts complex?”

“When are you going to turn your attention—and that expensive education of yours—to developments on the water? Water is over 70 percent of the world’s real estate, you know!”

Ted remembered how he had chafed at that last inquiry, biting back the urge to tell the old coot that this was precisely what he had hoped to do at Imago Bay, but Willis’ refusal to sell his property kept thwarting him.

Instead, deference to his grandfather and his own professionalism prompted Ted to respond with thoughtful, forthright answers. Willis usually countered with a curt “Humph.” Ted felt profound relief each time he stepped off the Rubicon.

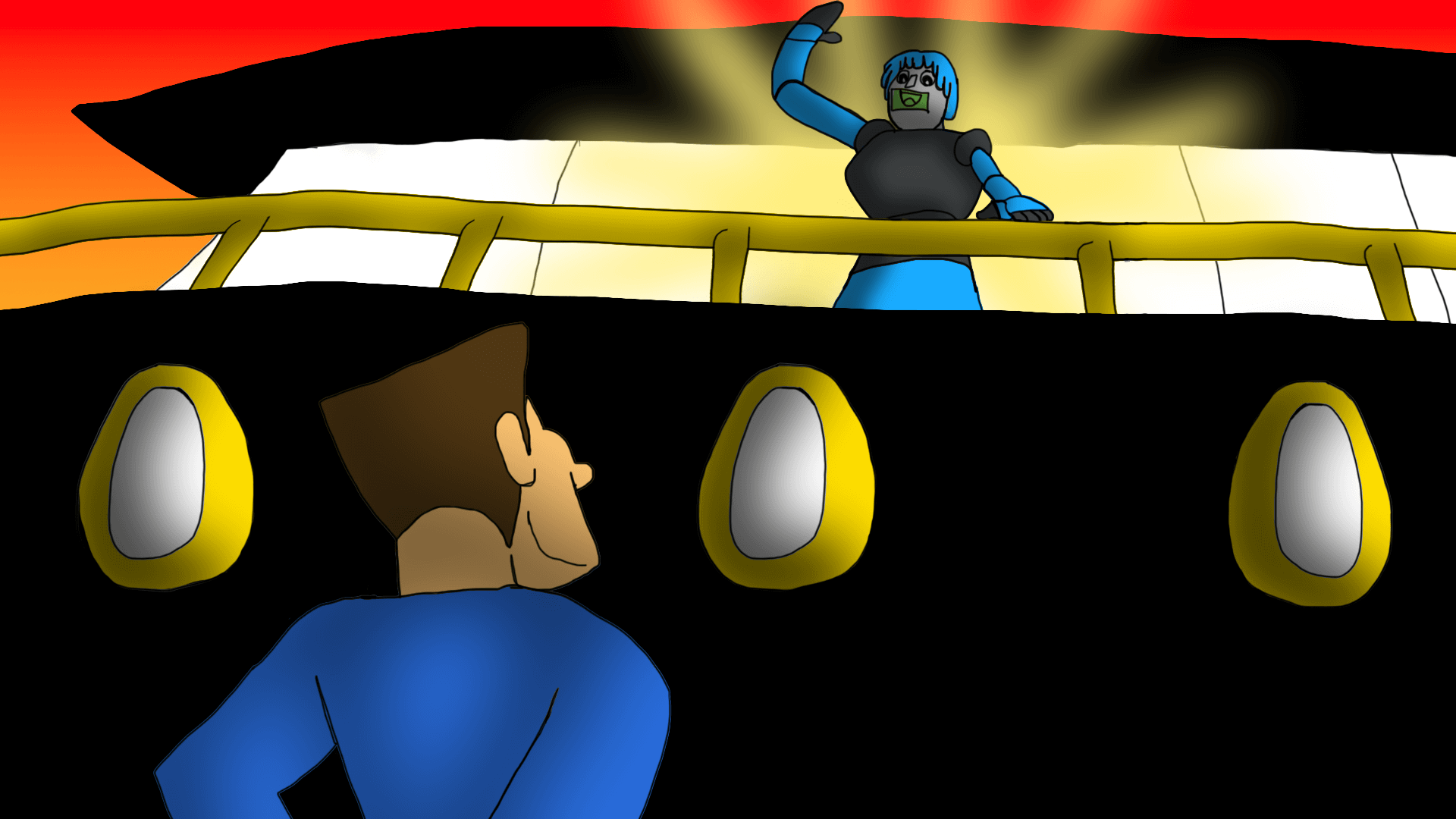

The next day, approaching the old boat brought back that familiar dread. He absentmindedly reached to repeat his grandfather’s three hull taps when a voice hailed him from the deck. Ted looked up, abruptly stopped, and nearly dropped his briefcase into the bay. Instead of the attorney he was expecting, the figure hovering (hovering!) above him was robotic, blue and silver, and addressed him in a voice that was somewhat mechanical and yet, absurdly, all female.

“Hello, you must be Ted Whitaker. I’m Aerobe. The rest are inside. Please join us.”

In all his previous visits, Ted had never ventured deeper into the Rubicon than the rather austere and worn outer deck. Now he found himself following a robot into a stateroom outfitted in burnished teak and gleaming brass.

Arnold Freeburg rose from one of the leather chairs flanking the long stateroom table, extended his hand to Ted, and gestured to him to have a seat. “Let me commence with the reading of Barnaby Willis’ last will and testament, and that will serve to introduce the rest of the people around the table.”

Ted nodded mutely, his mind a whirl of robots, teak hardwoods, brass, and an image of Ol’ Barnacle scowling at him.

But he listened intently to hear that the elderly loner had devoted much effort, time, and resources studying the ecosystem of Imago Bay, including water quality, aquatic life forms—both indigenous and migratory—and the projected effect that the development of Imago Bay into a floating community would have on that ecosystem. He was expecting the attorney to say that somehow the old boy had managed to invoke a permanent injunction to prevent the development of Imago Bay by Ted or anyone.

Instead, Freeburg dropped a bombshell in his lap.

“To the end of preserving the sanctity of marine life and water quality of Imago Bay, I am hereby bequeathing my entire holding of bayside property, including the vessel Rubicon, to Theodore Whitaker, to be developed n accordance with the following—.”

Ted interrupted the attorney’s narrative, “Did you just say that Bar—uh, Mr. Willis, has left his part of the bay to—me?”

“Quite right, Mr. Whitaker, but please understand that there are certain stipulations.” He continued reading. The remainder of Barnaby Willis’ testament expressed his desire that Imago Bay be developed into a paradigm for all that a floating community should be. Further, it urged that this development establish standards for wastewater treatment that could be implemented statewide and ultimately adopted all along the coast.

At this point the attorney referenced the two representatives from the county and state environmental offices that had oversight for regulatory compliance. “Ross Paulson and Genevieve La Boite will be an ongoing advisory component of the development process, helping to craft the regulatory standards as this floating community comes to fruition.”

Ted nodded to them. He was already familiar with Ross Paulson from zoning hearings; they generally found themselves on the same side of any argument.

Freeburg continued, “Also part of the advisory committee is the wastewater expert you met at the beginning of our meeting” He gestured to Aerobe.

Freeburg concluded his reading and rose to leave, “Mr. Whitaker, you and whatever staff you assign, plus myself and Barbara Adams from my office, and the aforementioned parties will compose the Imago Bay Development Committee per Barnaby Willis’ wishes. With your permission, we’ll set up a proposed meeting schedule and forward it to your office. Please contact me if you have questions.”

Then he handed a heavy key ring with labeled ignition and hatch keys to the Rubicon to Ted.

Ted shook hands and with the attorney, his staff, and the regulatory officials as they left the stateroom.

Aerobe approached Ted and asked, “May I show you something?”

Ted looked around as they traversed the length of the boat. While obviously old, the vessel was spotlessly appointed, and lovingly restored. It was, Ted thought, an unexpected treasure.

She led Ted to an installation just off the engine room.

“This looks much newer than its surroundings,” Ted commented.

Aerobe told him. “It’s a MarineFAST® sewage treatment system. He had it installed last year.”

She explained that all blackwater and Graywater from the ship’s head and galley were piped to the MarineFAST® unit where raw sewage was converted into water that was treated and disinfected so it could be safely discharged directly into the water, in accordance with Coast Guard regulations.

Ted exclaimed, “Incredible! Did you work with him on that?”

“Yes,” Aerobe replied, handing him a folder of MarineFAST® brochures, fact sheets, and case studies, “Mr. Willis seemed quite pleased with this solution. Then he asked if I would be part of a consortium to put some teeth into development regulations on the waterfront. That’s the group you just met.”

“I had no idea that Ol’ Bar—,” Ted caught himself and stopped speaking.

“Ol’ Barnacle?” Aerobe asked

“You knew about that?” Ted asked, startled.

“Yes, he actually referred to himself that way on occasion. He said it was what a friend’s grandson called him. I think it amused him.”

As they walked back to the deck, Ted realized how little he actually knew the old man. He remembered again all the questions Barnaby Willis used to throw at him during his annual visits. He understood now that they had been a test of Ted’s own commitment to the issues that mattered most to Barnaby—water quality and the preservation of the marine ecosystem, not just for today but for decades to come. Apparently, he had gleaned that Ted loved the bay as much as he did.

Suddenly Ted began smiling, and his smile grew as Aerobe gently lifted off above the Rubicon and glided into the sky over Imago Bay.

That evening, Ted pored over the MarineFAST® materials Aerobe had given him. The more he read, the more convinced he became that this simple and robust system had the potential to set the wastewater treatment standard for the floating community he’d always envisioned for Imago Bay.

Then he reached for the fat folder of well-worn plans and drawings for Imago Bay that he’d painstakingly created over the years, all the while thinking it an exercise in futility. Tonight he viewed them in a fresh, optimistic light, not unlike the way he now saw Barnaby Willis. In less than 24 hours, Barnaby Willis had transformed from a reclusive contrarian into an impassioned, albeit somewhat eccentric, visionary.

The folder’s title flap was blank. Ted had never before dared to give his dream a name. Reaching for a marker, he carefully lettered Barnaby Bay onto the tab. This may eventually change, Ted thought, but for now it seemed like the perfect working title.